Nobody enjoys pain. It looms as a constant threat in the back of our minds, driving us away from danger and toward the comfort of our personal safe space. Yet, it is exactly this innate desire that paralyses us. The dread we feel in anticipation of pain robs us of our ability to embrace risk, take action, and become our highest selves. It would take a rare individual to cast aside this deep-seated impulse in favour of that which is uncomfortable, painful, and dangerous.

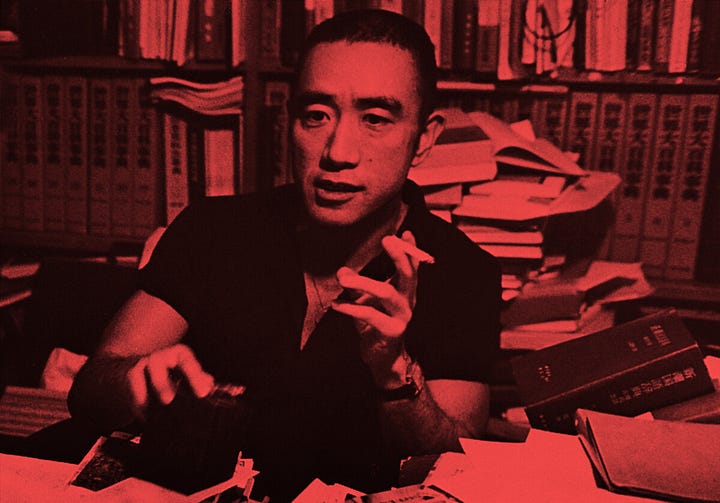

Yukio Mishima - Japan’s most radical traditionalist of the post-war period - made this approach his life’s philosophy, as outlined by his autobiography, Sun and Steel (1965). This seminal work of literature depicts the author’s transformation from a withdrawn weakling into a man of action, living and dying by the ideals of his Samurai ancestors.

The Age of Comfort

Such ancient warrior creeds directly oppose the structure of our contemporary lifestyles. In times where many feel helpless when faced with dystopian social climates, increasing violence, and bleak life perspectives, everything becomes centred on the avoidance of discomfort. Our basic mode of operation is to move from one “cosy” distraction to the next. Lulled in a flood of endless social media timelines, video game or streaming binges - all while stuffing ourselves with highly palatable slop foods and petty drugs - we seem to be caught in a permanent limbo somewhere between living and sleeping. All to avoid the mere possibility of emotional and physical pain, which the outside world threatens to inflict on our sensitive souls.

From an evolutionary perspective, this makes perfect sense. Pain is a signal that something harmful is coming our way, and therefore, it is best to rapidly correct whatever behaviour puts us in this circumstance. But when viewed from a deeper metaphysical perspective, it becomes clear that it is not just the potential for damage that frightens us when we experience pain. Pain becomes a harbinger of doom, as it is the closest sensation of death that we can perceive with our living senses.

Feeling pain is understanding that we are vulnerable to harm. Understanding that something can harm us implies that we are mortal. And nothing frightens us more than the short moments of clarity in which we come to terms with the innate limitation of our existence; those in which we feel that our mortality is, in fact, painfully real.

This anxious state of mind is unique to highly materialistic cultures. Throughout history, man could rely on his deeply held spiritual belief in a higher transcendental purpose to protect him from the existential dread when faced with his physical annihilation. But as men raised in societies that value nothing more than economic productivity and the expansion of our lifetime wealth, what could move us more than the originator of these supposed “values”?

It is the body, with its base desires, that entices us to become mere cogs in the great gearbox of hyper-commoditised 21st-century consumerism. Postmodern lifestyles sacrifice any traditional value in favour of those that align with satisfying our craving for physical and mental comforts the most. Progress has been reduced from the aspiration of the human spirit towards achieving its highest expression, down to a purely utilitarian calculation towards material equity and the ideological baggage that this distorted outlook carries.

Japan’s Westernisation After the Second World War

Such sentiments were not limited to the West. They were quickly taking hold of the Japanese culture after its defeat by the Allied Forces in 1945.

Mishima - a profound patriot until his last breath - quickly realised that his beloved nation was never going to be the same after the occupation began. It ushered in a new chapter in its history, one that would challenge even this profoundly spiritual nation, which, since the 17th century, had valiantly withstood the pervasive pressures of globalisation.

Historically, Japan had been ruled as an absolute monarchy by dynasties of emperors going back at least a millennium and a half. This made the civilisation that developed on the stunning Pacific archipelago one of the oldest surviving ones in the world by the time the 20th century rolled around. No other place throughout history had so much time in relative stability to develop an idiosyncratic culture paired with a homogenous group of inhabitants. Japan truly was the outlier in a world that had become increasingly globalised since the turn of the 15th century. But that was finally coming to an end.

The American conquerors ensured that the poison seed of materialism would take hold, radically restructuring the organic foundations of society to “spread Western ideals” to the deeply traditional Japanese population. What once was sacred, such as the institution of the monarchy itself and the ethno-religion of Shinto, had to be neutralised to accommodate the progressive visions of the new American overlords.

And so the Japanese experienced not just physical pain - the loss of millions in savage campaigns of conquest and violent retaliation by the Allies in places such as Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Tokyo - but crucially, the loss of a spiritual identity and the higher purpose that it had historically provided.

The Sun as Embodiment of Death

It was during the final act of this human tragedy that a young Mishima had his first experience with pain up close. As he described it, it was the sun that illuminated the cruel reality of armed conflict, from the metallic objects of warfare to the blood gushing from the bodies of their victims. The extent of the suffering revealed by daylight traumatised the boy to a point where he retreated into the safety of his room.

Instead of embracing the physical world and the painful forces it enacts on its many figures, like so many of us today, Mishima turned towards the abstraction of purely mental pursuits in the comfort of his home. Dreading the outside world and, in particular, the sun, which was its bright burning symbol, he became an intellectual. It was the nightly darkness that provided him a numbing shelter from the painful reality that we as men must inevitably face up to someday in our short lives.

It was only after years of reclusive authorship that Mishima realised that the rejection of the physical world had transformed him into an entirely helpless being by the time he had turned 30. The author intuitively concluded that this was not just a problem distinct to himself, but one that had started to plague the vast majority of Japanese men. Towards the end of his life, he summarised in Sun and Steel:

“The estrangement of body and spirit in modern society is an almost universal phenomenon.”

- Yukio Mishima, Sun and Steel (1965)

He had become the sad real-life expression of this, as his frail body was deteriorated through years of escaping into the sheltered darkness of his nightly studies.

Mishima’s epiphany was that the intense focus on nocturnal activities, born from his fear of the real world, was dissociating him from his own body. It was the sun, his old enemy, that had kept him indoors, away from the pain of reality. However, more importantly, this mental retreat also kept him from taking the necessary action, which would have otherwise transformed him into an entirely different man.

The Steel as Embodiment of Endurance

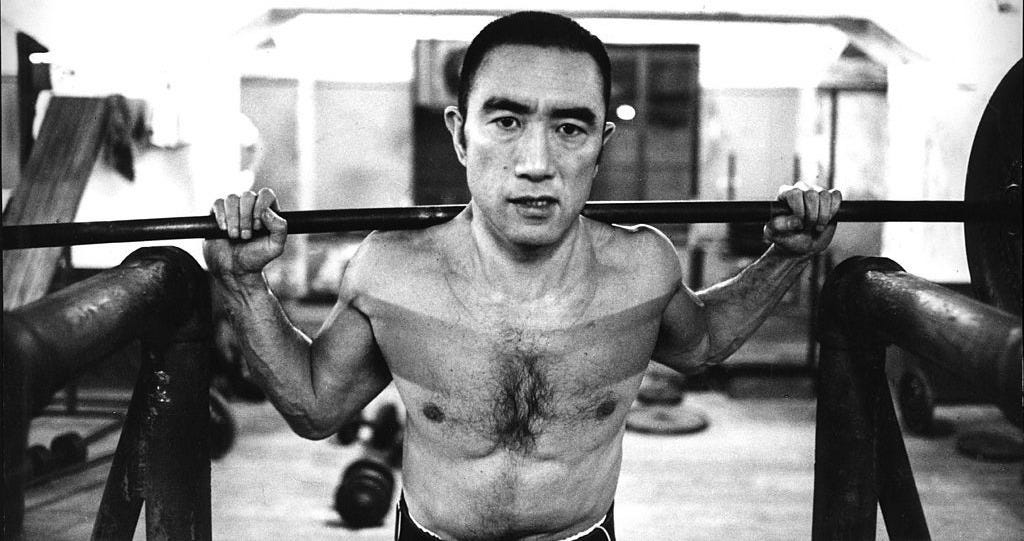

It was his physical inferiority that had alienated the young Mishima from his body, the vessel through which we engage with the real world. And so, he rediscovered steel - the very material that, illuminated by the sun, his younger self had once witnessed as an agent of mass destruction.

Steel possesses an innate duality: depending on the force applied, it can either build the human body through disciplined exertion or destroy it with unrestrained violence. Yet, despite of this danger, one cannot transform the body by merely existing in a mental vacuum. Growth demands the application of force with steel and the endurance of the resulting pain. It was through the habitual infliction of this constructive pain upon himself that Mishima not only emerged from the darkness of his room but, more crucially, escaped the clouded darkness of his mind.

Physical training with steel - namley bodybuilding - enabled the once-meek intellectual to reunite body and soul, allowing him to break free from his withdrawn existence. The gradual increase in weight mirrored the steady development of his once-meagre musculature, marking a path of discomfort that led to his fundamental transformation. Over time, he evolved from a frail 30-year-old into a robust man. More striking than his aesthetic metamorphosis was the profound shift in his mentality. The fears that had kept him caged - the danger of an uncertain world - diminished, as his growing physical fortitude instilled a newfound mental resilience into him.

When we are physically weak, we are easily overwhelmed, and fear takes root naturally, manifesting as reclusiveness and a lack of confidence. But as we grow stronger, our nascent mental fortitude grows similarly. Repeated exposure to pain eventually erodes our fear of it. Mishima himself came to understand that pain itself is the truest physical expression of existence. While the intellectual contemplates the meaning of death, the man of action actively seeks out pain as its manifestation in the physical world and, in doing so, begins to grasp its true gravity.

Rather than retreating indoors in pursuit of comfort, Mishima shows that men must embrace resistance training. Physical progress demands progressively overloading the body with forces rarely encountered in daily life. By willingly subjecting ourselves to the discomfort of lifting, we make all of life’s challenges more bearable. This practice brings us closer to understanding the suffering inherent in existence. Steel teaches men to grow through adversity, to endure, and ultimately, to cultivate a more authentic relationship with death - symbolized, in Mishima’s metaphor, by the sun.

Embracing The Way of the Heroic Warrior

At one point, Mishima points out that the cult of the archetypal hero is frequently derided by the weak. This is an expression of the various insecurities inherent to the frail who cannot visualise themselves as anything but weak and incapable when confronted with a heroic burden.

It is the hero who is the ultimate testimony to the natural endpoint of human endurance, which would easily break any mediocre man. Therefore, it is unsurprising that the hero is defined by a willingness to make the ultimate sacrifice in his confrontation of evil, with nothing but the expectation of prevailing as the superior being.

Suppose the hero should fail in his endeavour, however. In that case, it is his sculpted physique that, in the moment of death, develops a romantic component: The destruction of that which has been developed through pain and suffering in a final act of selfless sacrifice. It lies in the hero’s nature to embrace the tragedy of dying beautifully in the prime of his life. Mishima hoped that he would meet such an aesthetic end for himself and therefore made an art out of bodybuilding for death.

Such a mindset defies the spirit of the materialist society, which attributes the highest value to the body and its physical needs. It stands in complete opposition to the mentality of the average Western man, who avoids difficulty at all costs and hopes to deteriorate into old age, ideally with the least amount of discomfort. This, of course, also implies that all dangers of life and the related suffering are to be avoided. Never taking any risks, never going through any hardship, necessarily means that most men will lead a life without ever having done anything truly impactful.

To Mishima, a strong desire to grow old is a symptom of a society that has replaced the idol of the spiritual and energetic warrior with that of the materialistic and lethargic consumer.

Language Distorts Reality, Exercise Restores It

Sun and Steel highlights the danger of embracing the intellectual over the physical, as the latter is firmly rooted in reality, while the former is simply abstracting it.

Mishima witnessed the rise of Japanese communism in the 1950s and 60s with great disdain. The egalitarian cult built its foundation on a utopian world view that relied heavily on a degree of reality distortion that could only be achieved through the power of language. It was exactly the type of man bred by postmodern society, conditioned to prize abstraction and deconstruction above the tangible and the particular, that was susceptible to this kind of thinking. Leftists claim to desire a classless society, but in practice require two classes to implement their vision:

A servile herd of weak and sedentary subjects - the kind that prefers to waste its time with apathetic escapism and meaningless slop entertainment.

An elite of intellectual word architects of all kinds - politicians, journalists, academics, lawyers and bureaucrats, who keep the masses distracted through linguistic acrobatics.

It is no surprise, then, that they have always despised the ability of physical fitness to animate the spirit and clear up the mind. The Soviets went so far as to ban bodybuilding entirely in the 1970s, since the idea of an individual man rising above his peers in such a blatantly visible manner was simply too dangerous a symbol for Russian Apparatchiks.

Even to this day, leftists regularly attempt to kick off moral panics about young men getting into bodybuilding for its inherent ability to “radicalise”. In doing so, they of course reveal their preference to govern confused consumers and not clear-thinking citizens. They fear nothing more than the man of action - he who lives in the sun, which reminds him of his mortality, granting him clarity of direction, and making him physically capable through exercise to pursue such a higher purpose to its natural end.

Becoming a Man of Action

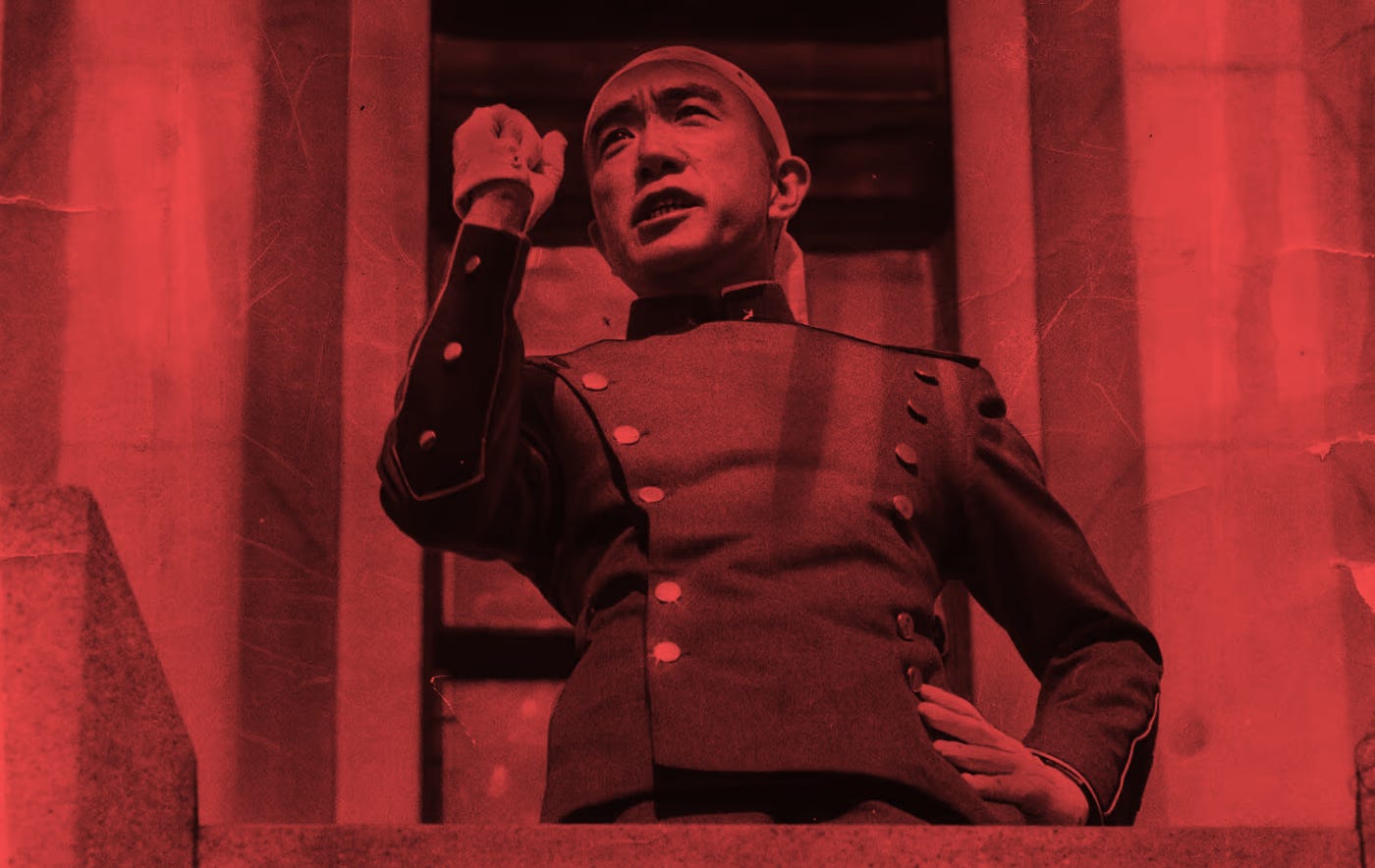

Ultimately, it is important to realise that Mishima’s entire philosophy was one founded on taking action. He did not simply muse on abstract concepts in Sun and Steel, but rather used the autobiography as a statement of intent. His life was one marked by a desire to not just exist, but to live intentionally guided by a framework of higher principles. In his worldview, apathy represented the greatest possible sin.

In 1970, inspired by his traditionalist ideals, Mishima stormed the headquarters of the Japanese armed forces and encouraged the military to reinstate the emperor Hirohito to political power. Ironically, this effort failed because the present audience of soldiers was utterly disinterested in facing any adversity in the name of a higher purpose. For the dishonour of failing the emperor, Mishima ended his own life by committing seppuku in the tradition of the ancient Japanese warrior cult of the Samurai.

After his death, Mishima became a symbol of resistance for the Japanese right. His self-sacrifice represents the consequence of a philosophy which recognises the finality of material existence and subordinates it to the eternal realm of the metaphysical absolute. The hero does not fear death, but embraces it at the very peak of his life, if it should come for him while making a full-hearted effort in the pursuit of something deeply meaningful.

Sun and Steel, despite of its esoteric language conveys a clear message to the contemporary reader - to fight back against intellectual escapism, against hollow materialism and the deterioration of the body and soul through nihilistic apathy. Mishima’s entire life embodied the transmutation of these ideas into action.

For those of us who have grown sick and tired of the soulless monotony that is postmodern life, it is not enough to simply mull over this conclusion. As men, we should embrace the pain of action. Start by lifting steel neither for vanity nor for status and not purely for health, but counterintuitively to grasp the finiteness of your existence. The act of lifting weights should not constitute the simple exchange of time for muscle. For Mishima, bodybuilding and martial arts became an act of rebellion against the abstraction of words and signified his arc from a night dwelling intellectual into a man of action who embraced the sun - the great illuminator of our harsh, physical reality.

Don’t forget to like, restack and leave your thoughts in the comments.

Grandiose

This is beatiful, thank you for writing it